One of the primary forms of Dionysos venerated within the Starry Bull tradition is referred to by his epikleseis Eubouleos meaning “He of Good Counsel” and Epikoos “He who Listens.” In Bacchic Orphism Dionysos intercedes on behalf of the initiate, speaking words to soothe the ancient grief of Persephone which must otherwise be atoned for through purgation and punishment:

For from whomsoever Persephone shall accept requital for ancient grief, the souls of these she restores in the ninth year to the upper sun again; from them arise glorious kings and men of splendid might and surpassing wisdom, and for all remaining time men call them sainted heroes. (Pindar, fragment preserved in Plato’s Meno)

The happy life, far from a vagrant existence, that is desired by those who, in Orpheus, are initiated through Dionysos and Kore and told to cease from the circle and enjoy respite from disgrace. (Proklos, Commentary on Plato’s Timaeus 3.296.7)

Dionysos is the cause of release, whence the God is also called Lusios. And Orpheus says: “Men performing rituals will send hekatombs in every season throughout the year and celebrate festivals, seeking release from lawless ancestors. You, having power over them, whomever you wish you will release from harsh toil and the unending goad.” (Damascius, Commentary on the Phaedo 1.11)

Now you have died and now you have been born, thrice blessed one, on this very day. Say to Persephone that Bakchios himself set you free. A bull you rushed to milk. Quickly, you rushed to milk. A ram you fell into milk. You have wine as your fortunate honor. And rites await you beneath the earth, just as the other blessed ones. (Gold tablet from Pelinna)

Likewise he is the one who intervenes when none of the other Gods can break the cycle of violence and recrimination that Hera and Hephaistos find themselves trapped in:

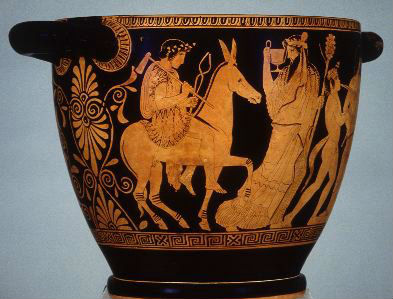

Hera hurled Hephaistos down from heaven, ashamed at her son’s lameness, but he made use of his skill. Having been rescued in the ocean by sea divinities he made many glorious things – some for Eurynome, some for Thetis, by whom he had been saved – but he also built a throne with invisible chains and sent it as a gift to his mother. And she was very delighted with the gift and she sat on it and found herself trapped, and there was no one to release her. A council of the Gods was held to discuss returning Hephaistos to heaven; for as they thought he was the only one who could release her. So while the other Gods remained silent and were at a loss for a solution, Ares undertook to do something, and when he got there, he accomplished nothing, but quit in disgrace when Hephaistos threatened him with blazing torches. Since Hera was in such great distress, Dionysos came with wine and, by making Hephaistos drunk, compelled him to follow through persuasive speech. When he came and released his mother he made Dionysos Hera’s benefactor, and she, rewarding him, convinced the heavenly Gods that Dionysos, to should be one of the heavenly Gods. (Libanios, Progymnasmata Narration 7)

In the mortal realm Dionysos is the one who gives voice to those who suffer and have been deprived of all other outlets, usually resulting in the institution of a festival that makes the community that spurned them reenact their story, as he did with Erigone:

When Ikarios was slain by the relatives of those who, after drinking wine for the first time fell asleep (for as yet they did not know that what had happened was not death but a drunken stupor) the people of Attika suffered from disease, Dionysos thereby (as I think) avenging the first and the most elderly man who cultivated his plants. At any rate the Pythian oracle declared that if they wanted to be restored to health they must offer sacrifice to Ikarios and to Erigone his daughter and to her hound which was celebrated for having in its excessive love for its mistress declined to outlive her. (Aelian, On Animals 7.28)

And the Oinotrophoi:

My lord, most noble hero, you make no mistake. You saw me father of five children, now such is the fickleness of fate you see me almost childless. For what help to me is my son far away on Andros isle where in his father’s stead he reigns? Delius gave him power of prophecy and Liber gave my girls gifts greater than the prayers of their belief. For at my daughters’ touch all things were turned to corn or wine or oil of Minerva’s tree. Rich was that role of theirs! But when it was known to Atrides, plunderer of Troy, with force of arms he stole my girls, protesting, from their father’s arms and bade them victual with that gift divine the fleet of Greece. They fled, each as she could, two to Euboea, two to their brother’s isle, Andros. A force arrived and threatened war, were they not given up. Fear overcame his love and he gave up his kith and kin to punishment. And one could well forgive their frightened brother … Now fetters were made ready to secure the captured sisters’ arms: their arms still free the captives raised to heaven, crying “Help! Help, father Bacchus!” and the God who gave their gift brought help, if help it can be called in some strange way to lose one’s nature. How they lost it, that I never learnt, nor could I tell you now. The bitter end’s well known. With wings and feathers, birds your consort loves, my daughters were transformed to snow-white doves. (Ovid, Metamorphoses 13. 631 ff)

And Charilla:

The Delphians celebrate three festivals one after the other which occur every eight years, the first of which they call Septerion, the second Heroïs, and the third Charilla. The greater part of the Heroïs has a secret import which the Thyiads know; but from the portions of the rites that are performed in public one might conjecture that it represents the evocation of Semele. The story of Charilla which they relate is somewhat as follows: A famine following a drought oppressed the Delphians, and they came to the palace of their king with their wives and children and made supplication. The king gave portions of barley and legumes to the more notable citizens, for there was not enough for all. But when an orphaned girl, who was still but a small child, approached him and importuned him, he struck her with his sandal and cast the sandal in her face. But, although the girl was poverty-stricken and without protectors, she was not ignoble in character; and when she had withdrawn, she took off her girdle and hanged herself. As the famine increased and diseases also were added thereto, the prophetic priestess gave an oracle to the king that he must appease Charilla, the maiden who had slain herself. Accordingly, when they had discovered with some difficulty that this was the name of the child who had been struck, they performed a certain sacrificial rite combined with purification, which even now they continue to perform every eight years. For the king sits in state and gives a portion of barley-meal and legumes to everyone, alien and citizen alike, and a doll-like image of Charilla is brought thither. When, accordingly, all have received a portion, the king strikes the image with his sandal. The leader of the Thyiads picks up the image and bears it to a certain place which is full of chasms; there they tie a rope round the neck of the image and bury it in the place where they buried Charilla after she had hanged herself. (Plutarch, Aetia Graeca 12)

And Kyanê:

To Dionysos alone did Kyanippos, a Syracusan, omit to sacrifice. Then one day in a fit of drunkenness he violated his daughter Kyanê in a dark place. She took off his ring and gave it to her nurse to be a mark of recognition. When the Syracusans were oppressed by a plague, and the Pythian God pronounced that they should sacrifice the impious man to the Averting Deities, the rest had no understanding of the oracle; but Kyanê knew, and seized her father by the hair and dragged him forth; and when she had herself cut her father’s throat, she killed herself upon his body in the same manner. So Dositheüs in the third book of his Sicilian History. (Plutarch, Greek and Roman Parallel Stories 18)

And numerous others.

Indeed, one of the central tenets of tragedy is that μίμησις brings about κάθαρσις, as Aristotle remarks in the Poetics:

Tragedy, then, is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude; in language embellished with each kind of artistic ornament; in the form of action, not of narrative; through pity and fear effecting the proper purgation of these emotions.

For the Greeks language had a potent magical force to it:

Fearful shuddering and tearful pity and sorrowful longing come upon those who hear it, and the soul experiences a peculiar feeling, on account of the words, at the good and bad fortunes of other people’s affairs and bodies. But come, let me proceed from one section to another. By means of words, inspired incantations serve as bringers-on of pleasure and takers-off of pain. For the incantation’s power, communicating with the soul’s opinion, enchants and persuades and changes it, by trickery. Two distinct methods of trickery and magic are to be found: errors of soul, and deceptions of opinion. (Gorgias, Encomium of Helen)

A force that is still being felt millennia later, as Michael Meade’s use of tragic plays to heal wounded soldiers so ably demonstrates:

A soldier returns home from battle but has brought the war with him. He stares off into the distance, unable to take joy in his family or friends, still hyperalert to threats he no longer faces. Unable to heal his invisible wound, he takes his own life. This isn’t a tragic news story about a veteran coming back from Afghanistan with a case of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It’s a summary of the Greek play “Ajax,” which is more than 2,000 years old.

The Greeks didn’t call it PTSD. But they understood that war brought trauma (from the Greek word meaning “wound”), which left some warriors with a thousand-yard stare long after they returned home. Advocates and the military itself have found that ancient myths and stories like “Ajax” can help veterans and active-duty soldiers cope with the overwhelming psychological stress that the country’s longest war has put on its relatively small volunteer force.

[…]

Meade calls himself a “mythologist,” and he uses ancient stories from Ireland, Greece, India and other cultures to prod veterans into unloading their experiences and making sense of them over four-day retreats on the West Coast. Veterans in Meade’s program also sing ancient warrior chants together, take part in a “forgiveness” ceremony, and write and recite poetry. He believes that many ancient cultures did a better job of formally welcoming returning warriors home and helping to collectively shoulder some of their burdens.

“Everyone wants to tell their story,” Meade said. “Even the most wounded people, given the chance, want to tell the story of that wound. A wound is like a mouth.”

May our Lord Dionysos bring his healing and redemptive madness to all those who are in need it:

Madness can provide relief from the greatest plagues of trouble that beset certain families because of their guilt for ancient crimes: it turns up among those who need a way out; it gives prophecies and takes refuge in prayers to the Gods and in worship, discovering mystic rites and purifications that bring the man it touches through to safety for this and all time to come. So it is that the right sort of madness finds relief from present hardships for a man it has possessed. (Plato, Phaedrus 244de)